14 July 2022 - Phytase producers previously promoted their products by using the simple argument that phosphate resources were depleting and should be spared. However, the end of phosphate production is probably not that close.

According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), global reserves of phosphate rock amount to more than 300 billion tonnes. In addition, phosphorous is one of the most abundant elements and is found everywhere. So what's the problem then?

The issue is not in finding phosphate rock but in finding phosphate ore containing high phosphate levels and in the form of bone phosphate of lime.

Most industrial phosphate production uses high-grade phosphate rock. Unfortunately, these high-grade deposits are not found in many places. Morocco owns about 70% of the known reserves. Among rock producers, quality varies greatly, from pure volcanic rock found in Finland or Russia to radioactive sedimentary deposits containing high levels of heavy metals.

According to the USGS, five countries control 85% of the world’s phosphate rock reserves: Morocco (70%), China (5%), Egypt (4%), Algeria (3%), and Syria (3%). In terms of the annual supply of phosphate rock, just four countries were responsible for 72% of global production in 2021: China (39%), Morocco (17%), the US (10%), and Russia (6%)

Today, technology to extract the phosphorous from low-grade deposits is expensive or not scalable. Though this might change in the coming years, for the time being, the world is reliant on smaller resources than one might think.

One issue with existing technologies used to produce phosphates is that they are far from being environmentally friendly. Problems include emissions of sulphur oxides into the air, mine tailing, and eutrophication.

Therefore, it's fair to say that a better option would be to reduce the use of phosphates and look for alternatives. In that respect, phytase can help by lowering inclusion levels in feed and application rates on crops with the help of precision farming techniques.

We hear from the field that consumption has been heavily reduced, and soon feed phosphates may become niche products in pig feed, for instance. But can we see it from statistics?

To answer this question, Praxed looked to the UK, where modern agriculture has been developed during the last two centuries. As there are no official statistics on detailed consumption of feed phosphates in the country, we used trade statistics to calculate the net consumption of phosphates compared to feed production levels.

During the last 20 years, the UK has been through several crises, from the BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) crisis in 1992 to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

Nonetheless, feed production shows a positive trend and is growing, especially in poultry, where we see robust growth. The UK is still far from being self-sufficient in meat production, but efforts are being made to reach self-sufficiency in poultry. After a substantial decline, even pig production is now growing.

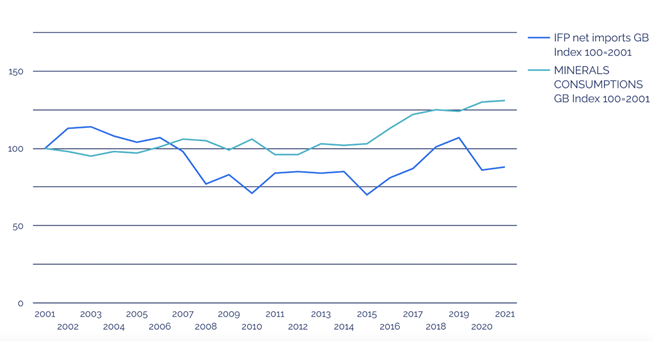

There is also clearly increased consumption of minerals in the country. However, looking at feed phosphate net imports, we see the opposite trend, with a significant drop after 2008 and, ever since, stagnant demand. Relative to other feed consumption, we see that the use of feed phosphate is declining. This illustrates well what we often hear when talking to nutritionists that phosphate consumption has been reduced.

|

Now, one might ask: will the war in Ukraine trigger another reduction in demand? Today it is hard to say; factors other than the price also affect demand. For example, there is a seasonality factor. And most recently, outbreaks of avian flu and African Swine Fever (ASF) have seriously impacted feed consumption. Finally, one can't ignore the global economic slowdown, inflation, and the impact on meat consumption. |

Guillaume Milochau |

Assessing feed phosphate demand elasticity is still possible. If the price goes up, consumption should decrease, and if the price goes down, it should increase unless substitutes exist. However, this is not the case for the feed phosphate market.

Feed phosphate production is one of the branches of the fertilizer industry. But fertilizer producers seem to overlook one crucial fact about animal nutrition: feed producers are constantly looking for substitutes to reduce costs, optimise performance and mitigate their environmental impact.

Analysing the UK market again and looking for a correlation between price and demand, we see that after the historical high phosphate prices in 2008, phosphate inclusion levels fell by 0.3-0.5%.

Later, even when prices decreased to low levels, volumes stagnated. Looking at the relative level of feed phosphate use to minerals production, we see declining demand at a time when prices were low compared to today.

IFP imports vs mineral consumption in the UK. Source: UK Stat

The combination of demand destruction and tight supply, with fears of product shortages lately due to the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, has forced the feed industry to reconsider its use of feed phosphates. As a result, Praxed expects to see a decline in consumption of feed phosphates, lower inclusion levels, and higher use of substitutes.

When looking outside Europe, we come to the same conclusion. For example, research in China shows a revision of the minimum inclusion levels for feed phosphate and the promotion of phytase, with two goals in mind: lowering costs and improving the environment.

Since China revised the minimum inclusion levels for feed phosphates and began promoting phytase in 2017, consumption of feed phosphates has declined by the equivalent of 1 million tonnes of MCP, according to the consultancy Praxed.

Perhaps, this is also where the phosphate industry fails. Instead of adapting production to market needs, producers are still looking to expand output as if phosphate demand will continuously grow along with food consumption and the global population.

From a fertilizer or crop nutrition point of view, the need for nitrogen, phosphorous, or potash, to name a few of the essential nutrients for plant growth, is increasing with food demand. Therefore, to some extent, fertilizer demand is inelastic. To achieve good yields, farmers must bring nutrients to the crops. Though actual high prices temporarily impact the market, producers know that demand will return and expand in the long run.

Most of the market studies done by feed phosphate producers when investing in new capacities are based on the same assumptions as the fertilizer industry. However, what applies to crop nutrition does not apply to animal nutrition.

Another explanation might be that when building new capacities for producing fertilizer, adding a feed phosphate unit does not represent a significant investment and is an excellent way to mitigate fertilizer business seasonality and optimise costs.

In some cases, feed phosphate production is a way to manage by-products such as hydrochloric acid from potash production (SOP).

Stay tuned for further details in Guillaume's next article in August, where he will analyse whether feed phosphates could be considered a by-product of the fertilizer industry.

Guillaume Milochau is Economic Intelligence Consultant of agricultural commodities, chemicals, and energy for Praxed, and provides a monthly insight on the phosphate industry for Feedinfo. All views are his own.